Bounded Contexts Are All About Cohesion

When we talk about Bounded Contexts in Domain-driven Design (DDD), the conversation often goes toward architecture, integration, or team ownership. We might discuss whether each Bounded Context maps to a microservice, or how they connect through context maps and relationships such as “Customer/Supplier” or “Conformist.”

All of that is valuable, but we run the risk of missing an essential perspective. This blog post aims to look at Bounded Context from a different angle: the Bounded Context not as a boundary around something, but rather as a boundary for something: a unified model with a specific purpose. And that purpose is what gives it cohesion.

Cohesion

The term cohesion predates software architecture by decades. Its Latin root coherere literally means “to stick together, to be connected.” And across disciplines — from chemistry to civil engineering, from sociology to linguistics, cohesion always describes forces of connection, the strength of ties, or the ability to form a stable whole.

In chemistry, cohesion is what keeps molecules of the same substance bound together.

In linguistics, cohesion is what turns words into meaningful sentences.

In social systems, cohesion keeps a community united around shared purpose and identity.

The similarities to software are in eyes sight: when the parts of our systems belong together for a clear reason, they are easier to reason about, to change, and to evolve. When they don’t, complexity leaks all over the codebase.

Cohesion in Software Design

In software architecture, cohesion describes how closely the elements within a module are related. A cohesive module contains elements that work together to accomplish one specific purpose. The less related the elements are, the weaker the cohesion — and the more likely it becomes that changes in one part create accidental ripples elsewhere.

Wayne P. Stevens, Glenford J. Myers, and Larry L. Constantine introduced the concept formally in their 1974 paper Structured Design. Their insight was simple yet profound:

“Coupling is reduced when the relationships among elements not in the same module are minimized. There are two ways of achieving this: minimizing relationships among modules and maximizing relationships among elements in the same module.”

The second part, which is about maximizing relationships among elements in the same module, is precisely what cohesion aims at.

The Seven Levels of Cohesion

Stevens, Myers, and Constantine (often referred to as SMC) describe seven levels of cohesion, ranging from the weakest to the strongest:

Coincidental Cohesion – Things grouped arbitrarily (“utility” modules that do random tasks).

Logical Cohesion – Functions grouped by similarity in kind (“all readers”, “all writers”).

Temporal Cohesion – Tasks grouped by when they happen (“startup”, “shutdown”).

Procedural Cohesion – Tasks grouped because they execute in sequence, but with different goals.

Communicational Cohesion – Tasks grouped because they operate on the same data.

Sequential Cohesion – The output of one part serves as input for another.

Functional Cohesion – Every part contributes to one clearly defined, unified purpose.

Note: On my GitHub is a project which showcases all levels of SMC-Cohesion on a class and package level: https://github.com/mploed/cohesion-examples

Functional cohesion stands at the top because it produces modules that make conceptual sense. A functionally cohesive module does one thing really well, it is specialized to a specific purpose.

Purpose: The Anchor Point of Cohesion

The authors of Structured Design offer a useful heuristic for checking if a module has functional cohesion:

“A useful technique in determining whether a module is functionally bound is writing a sentence describing the function (purpose) of the module, and then examining the sentence.”

If the sentence is short, active, and singular like “calculates mortgage eligibility” then the module probably has functional cohesion.

If the sentence needs several verbs, conjunctions, or subordinate clauses like “reads configuration, initializes services, and calculates totals” then it is most likely only logical or temporal bound.

This is a surprisingly powerful test. When we describe what a part of the system does, language itself betrays the design. The more we need to explain, the weaker the cohesion tends to be.

Heuristics for Recognizing Strong Purpose

Functional cohesion manifests in language. Some heuristics help identify it:

Singular verbs: “calculate,” “validate,” “approve.”

Multiple verbs hint at multiple responsibilities.

Clear object focus: “calculate loan risk,” “validate applicant data.”

If your sentence switches objects mid-way, cohesion breaks.

No temporal markers: “during startup,” “after saving.”

These indicate temporal cohesion rather than functional.

No conjunctions like “and/or”: every “and” adds ambiguity.

Stable purpose: changes to external behavior do not redefine what the module is for.

Functional cohesion means that the purpose is clear enough to act as a north star for design decisions. It gives the module its identity.

Domain-Driven Design: From Modules to Models

The SMC paper was written in the 1970s, long before Domain-Driven Design existed. Yet its central idea of grouping things that belong together because they serve a single purpose transfers seamlessly to the level of domain models.

In a DDD sense, a model is a conceptual module. It encapsulates not just code, but meaning. It represents a shared understanding of a part of the business, expressed through a ubiquitous language.

That language, which includes the words and concepts we use to describe the model, are the cohesive “forces” that hold it together. If you find yourself using many different vocabularies within one model, it’s may be an early warning sign that cohesion erodes.

Bounded Contexts as cohesive boundaries

The original idea of a bounded context can be broken down to the following sentence:

A Bounded Context is a boundary around a domain model which has a consistent (ubiquitous) language and which is tailored to a specific purpose.

That single sentence is packed with references to the basic concept of cohesion. It mentions consistency (shared language), boundary (deliberate scope), and purpose (why it exists). In my eyes a Bounded Context is most of all an inside view towards the model of a boundary which should reflect certain properties: consistent language and specialization towards one specific purpose. In other words: A model in a Bounded Context should have high cohesion, meaning that it forms a coherent whole around a single, unified purpose.

When you design a Bounded Context, you’re effectively designing for functional cohesion. The cohesive forces are not just technical dependencies; they are semantic, linguistic, and organizational.

The Bridge Between Purpose and Boundary

Cohesion gives us the micro-level principle: elements belong together when they contribute to one purpose. Bounded Contexts give us the macro-level structure: a boundary defines where one purpose ends and another begins. The bridge between the two is purpose. Purpose tells us what belongs inside the boundary and what should remain outside.

When we lose sight of purpose, our models grow incoherent. Suddenly, a Bounded Context contains too many ideas, too many languages, and too many goals. The result? Context leakage, semantic drift, and eventually accidental complexity.

Conversely, when a Bounded Context is designed around a strong, shared purpose, everything aligns:

The language becomes focused and unambiguous.

The model feels internally coherent.

Team conversations are crisp and domain-oriented.

Integration boundaries become clearer because what’s outside naturally feels like “not our purpose.”

That is cohesion at work: not in syntax, but in semantics.

The Power of Cohesion in Design

Why does all this matter? Because high cohesion at every level leads to designs that are easier to evolve and reason about.

In highly cohesive systems:

Change has a local effect. When you modify something, the impact stays within the context.

Language is consistent. The ubiquitous language naturally aligns with the purpose.

Teams have clarity. They can reason about their system boundaries without constant negotiation.

Complexity is localized. Each model can evolve independently based on its own rules and cadence.

In low-cohesion systems, everything tends to entangle. Purpose is wishy washy, language fractures, and teams spend their time coordinating instead of delivering.

That’s why cohesion is not just a “code quality” metric. It’s a guiding principle for strategic design.

When we design Bounded Contexts with high cohesion around a single, unified purpose and a consistent language, which can easily become ubiquitous, we create systems that are both structurally and semantically good. They are easier to understand, to maintain, and to evolve.

So next time you define a Bounded Context, don’t start with APIs or team charts. Start with a sentence. Write down what this model is for. If that sentence is clear, singular, and purpose-driven, you’re already halfway trhough towards functional cohesion and, in turn, towards a useful Bounded Context.

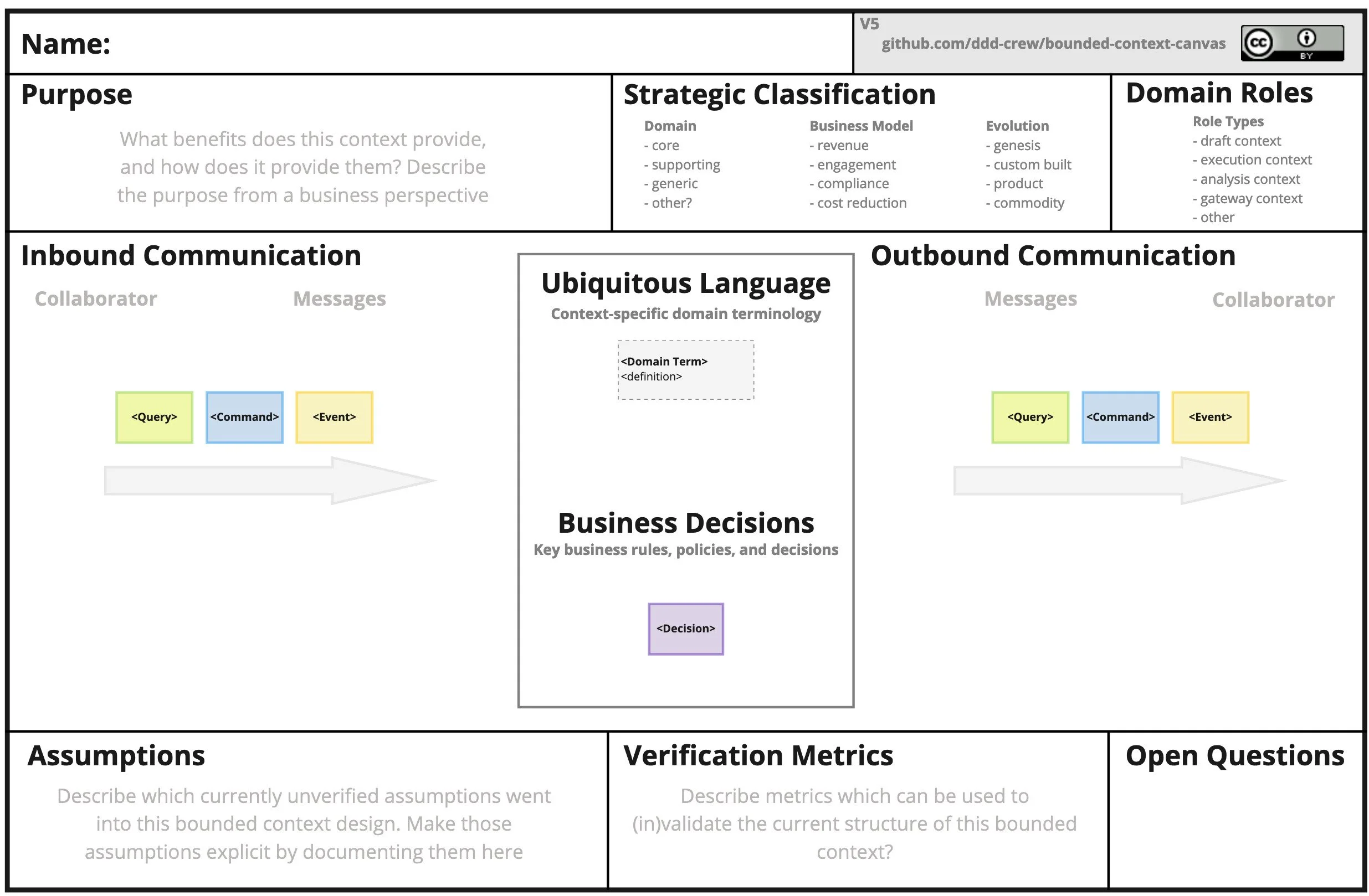

By the way: the Bounded Context Design Canvas from the DDD-CREW on GitHub has a field “purpose” for a very good reason ;-)